The chairman is working to finish the parts of the Farm Bill that were not included in the One Big Beautiful Bill.

On July 4, President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill into law. With it, most of House Agriculture Chairman G.T. Thompson’s Farm Bill became law.

Approximately 80% of the chairman’s Farm Bill priorities have been passed, and he is moving towards finishing the deal in the coming months.

Rep. Thompson, a Republican of Centre County, Pennsylvania, is working on a “skinny” Farm Bill to finish up reauthorizing key provisions for American farmers.

Thompson hopes the second bill will be passed out of his committee by the end of September.

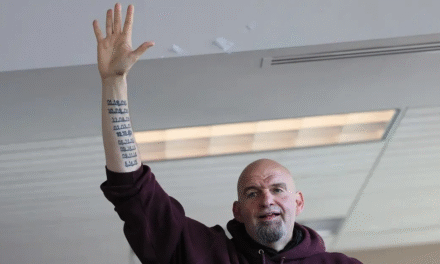

“I’ve been told all along, ‘Oh, you’re not going to be able to do this. You’re not going to do that. You’re not going to be able to accomplish this,’ And they’ve been wrong every time,” Thompson said at his annual ag summit on Monday at Central Pennsylvania Institute of Science and Technology.

“This legislation delivers on promises made to rural America. We put the farm back in the Farm Bill,” he added.

Among the critical provisions laid out in the One Big Beautiful Bill for farmers are an increase in funding for biosecurity and agricultural research at land-grant universities, as well as an increase in reference prices and creating 30 million base acres farmers can apply for.

Thompson is referring to the second part of the Farm Bill as “Farm Bill 2.0”. He hopes it will pass out of committee, being similar to a package the committee approved last year.

A piece of the package being debated is the “Save our Bacon” Act. The provision would strike down California’s Proposition 12, which requires pork and eggs sold in the state to be raised in accordance with its husbandry standards. This includes out-of-state products.

With the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill in July, Thompson made significant progress towards a legislative package he has been working on for several years.

The Farm Bill was signed into law in 2018 and expired in 2023.

This year’s Farm Bill is two years behind schedule. Every five years, the legislation expires and needs to be reauthorized by Congress. The process is contentious and often includes much debate until a final product is delivered to the president’s desk.